New research released on 22 July 2021 confirms Australia’s offshore wind resources offer vast potential both for electricity generation and new jobs. In fact, wind conditions off southern Australia rival those in the North Sea, between Britain and Europe, where the offshore wind industry is well established.

More than 10 offshore wind farms are currently proposed for Australia. If built, their combined capacity would be greater than all coal-fired power plants in the nation.

Offshore wind projects can provide a win-win-win for Australia: creating jobs for displaced fossil fuel workers, replacing energy supplies lost when coal plants close, and helping Australia become a renewable energy superpower.

The largest wind farm installation vessel in the world and the first turbine installed off the coast of Aberdeen in Scotland – Australia’s potential for offshore wind rivals that of the North Sea’s. Credit: Shutterstock

The time is now

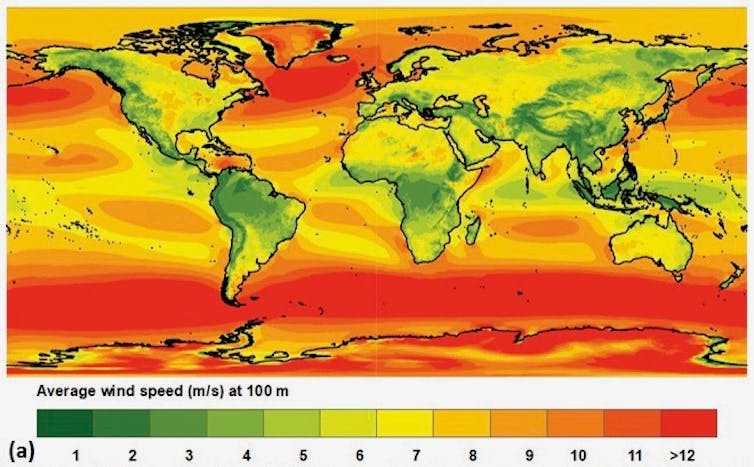

Globally, offshore wind is booming. The United Kingdom plans to quadruple offshore wind capacity to 40 gigawatts (GW) by 2030 – enough to power every home in the nation. Other jurisdictions also have ambitious 2030 offshore wind targets including the European Union (60GW), the United States (30GW), South Korea (12GW) and Japan (10GW).

Australia’s coastal waters are relatively deep, which limits the scope to fix offshore wind turbines to the bottom of the ocean. This, combined with Australia’s ample onshore wind and solar energy resources, means offshore wind has been overlooked in Australia’s energy system planning.

But recent changes are producing new opportunities for Australia. The development of larger turbines has created economies of scale which reduce technology costs. And floating turbine foundations, which can operate in very deep waters, open access to more windy offshore locations.

More than ten offshore wind projects are proposed in Australia. Star of the South, to be built off Gippsland in Victoria, is the most advanced. Others include those off Western Australia, Tasmania and Victoria.

Wind turbines can operate in deep waters. Credit: Shutterstock

Our findings

Our study sought to examine the potential of offshore wind energy for Australia.

First, we examined locations considered feasible for offshore wind projects, namely those that were:

- less than 100km from shore

- within 100km of substations and transmission lines (excluding environmentally restricted areas)

- in water depths less than 1,000 metres.

Wind resources at those locations totalled 2,233GW of capacity and would generate far more than current and projected electricity demand across Australia.

Second, we looked at so-called “capacity factor” – the ratio between the energy an offshore wind turbine would generate with the winds available at a location, relative to the turbine’s potential maximum output.

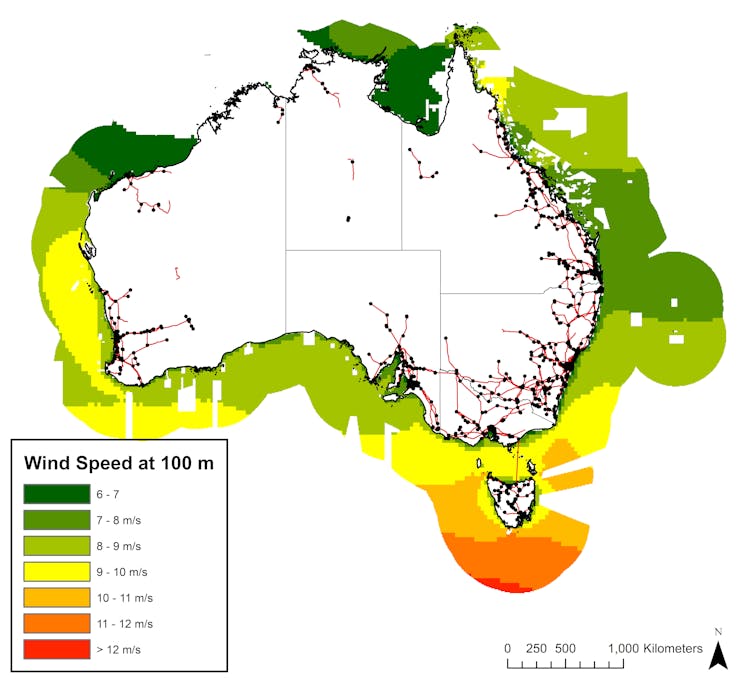

The best sites were south of Tasmania, with a capacity factor of 80%. The next-best sites were in Bass Strait and off Western Australia and North Queensland (55%), followed by South Australia and New South Wales (45%). By comparison, the capacity factor of onshore wind turbines is generally 35–45%.

Average annual wind speeds in Bass Strait, around Tasmania and along the mainland’s southwest coast equal those in the North Sea, where offshore wind is an established industry. Wind conditions in southern Australia are also more favourable than in the East China and Yellow seas, which are growth regions for commercial wind farms.

Average wind speed (metres per second) from 2010-2019 in the study area at 100 metres. Authors provided

Next, we compared offshore wind resources on an hourly basis against the output of onshore solar and wind farms at 12 locations around Australia.

At most sites, offshore wind continued to operate at high capacity during periods when onshore wind and solar generation output was low. For example, meteorological data shows offshore wind at the Star of the South location is particularly strong on hot days when energy demand is high.

Australia’s fleet of coal-fired power plants is ageing, and the exact date each facility will retire is uncertain. This creates risks of disruption to energy supplies, however offshore wind power could help mitigate this. A single offshore wind project can be up to five times the size of an onshore wind project.

Some of the best sites for offshore winds are located near the Latrobe Valley in Victoria and the Hunter Valley in NSW. Those regions boast strong electricity grid infrastructure built around coal plants, and offshore wind projects could plug into this via undersea cables.

And building wind energy offshore can also avoid the planning conflicts and community opposition which sometimes affect onshore renewables developments.

Global average wind speed (metres per second at 100m level. Authors provided

Winds of change

Our research found offshore wind could help Australia become a renewable energy “superpower”. As Australia seeks to reduce its greenhouse has emissions, sectors such as transport will need increased supplies of renewable energy. Clean energy will also be needed to produce hydrogen for export and to manufacture “green” steel and aluminium.

Offshore wind can also support a “just transition” – in other words, ensure fossil fuel workers and their communities are not left behind in the shift to a low-carbon economy.

Our research found offshore wind could produce around 8,000 jobs under the scenario used in our study – almost as many as those employed in Australia’s offshore oil and gas sector.

Many skills used in the oil and gas industry, such as those in construction, safety and mechanics, overlap with those needed in offshore wind energy. Coal workers could also be re-employed in offshore wind manufacturing, port assembly and engineering.

Realising these opportunities from offshore wind will take time and proactive policy and planning. Our report includes ten recommendations, including:

- establishing a regulatory regime in Commonwealth waters

- integrating offshore wind into energy planning and innovation funding

- further research on the cost-benefits of the sector to ensure Australia meets its commitments to a well managed sustainable ocean economy.

If we get this right, offshore wind can play a crucial role in Australia’s energy transition.

Authors

Sven Teske, Research Director, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney; Chris Briggs, Research Principal, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney; Mark Hemer, Principal Research Scientist, Oceans and Atmosphere, CSIRO; Philip Marsh, Post-doctoral researcher, University of Tasmania; and Rusty Langdon, Research Consultant, University of Technology Sydney.

This article has been republished from The Conversation under its Creative Commons license. Read the original article, published on 22 July 2021.