Scientists are uncovering the best truffles, what makes the healthiest artichokes, and where the most nutritious olive oil is produced in Western Australia.

Some foods, such as olive oil, may only have one ingredient, but its quality and health benefits hinge on a multitude of cultivation and harvesting processes.

Now researchers at the Health Futures Institute are using mass spectrometry and nuclear resonance spectroscopy to profile WA’s finest fare and pinpoint where healthier foods are being made.

While spectrometry has long been used to map things at the molecular level, Murdoch is programming new smaller desktop machines to profile plant compounds, such as polyphenols, in food samples taken from across the state.

Most plant-based foods contain polyphenols, which have powerful antioxidants and anti-inflammatory properties. In the plant, polyphenols protect against solar radiation or destructive pathogens.

But now a growing body of evidence suggests polyphenols may also prevent neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes, obesity, osteoporosis and some cancers in humans.

Biochemist, metabolic profiling expert and director of the Centre for Computational and Systems Medicine, Professor Elaine Holmes says the centre is discovering healthier food varieties and tailoring diet advice more precisely than ever before.

“It’s the ability to offer better dietary advice to people,” Professor Holmes said.

“Once we have these fingerprints and know what the benchmark for ‘good’ is, we can measure different products and their level of nutrition.”

Murdoch University’s Prof. Professor Holmes says her team are in the middle of mapping the chemical composition of hundreds of samples to uncover the molecular fingerprints of high-value foods, such as olive oil. Credit: Lenar Musin/ Shutterstock

Oil in the science

Professor Holmes says her team are in the middle of mapping the chemical composition of hundreds of samples to uncover the molecular fingerprints of high-value foods, such as olive oil.

“The first step is just to understand what’s in the olive oil and why are different olive oils chemically different,” Professor Holmes said.

“If you buy something from a little farm in Esperance, for example, is the olive oil from there always going to look the same? Have they got anything unique about them that could potentially be linked to health value?

“There are definitely differences in oils from different producers and you can separate by geographical location and by olive variety.

“Some are very distinctive in profile and have higher fatty acid composition. What we haven’t finished profiling yet is the polyphenolic composition, which is more likely to be linked to the health claims.”

While fatty acids, such as omega-3 and oleic acid, are known to reduce the risk of heart disease, polyphenolic compounds are the new frontier of nutrition because they can help in the prevention of neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes, obesity, osteoporosis and even the development of some cancers.

Professor Holmes remained tight-lipped about naming which producers have the healthiest olive oil but she revealed that the study, which is due for completion in March 2022, also looks at the quality of artichokes and truffles.

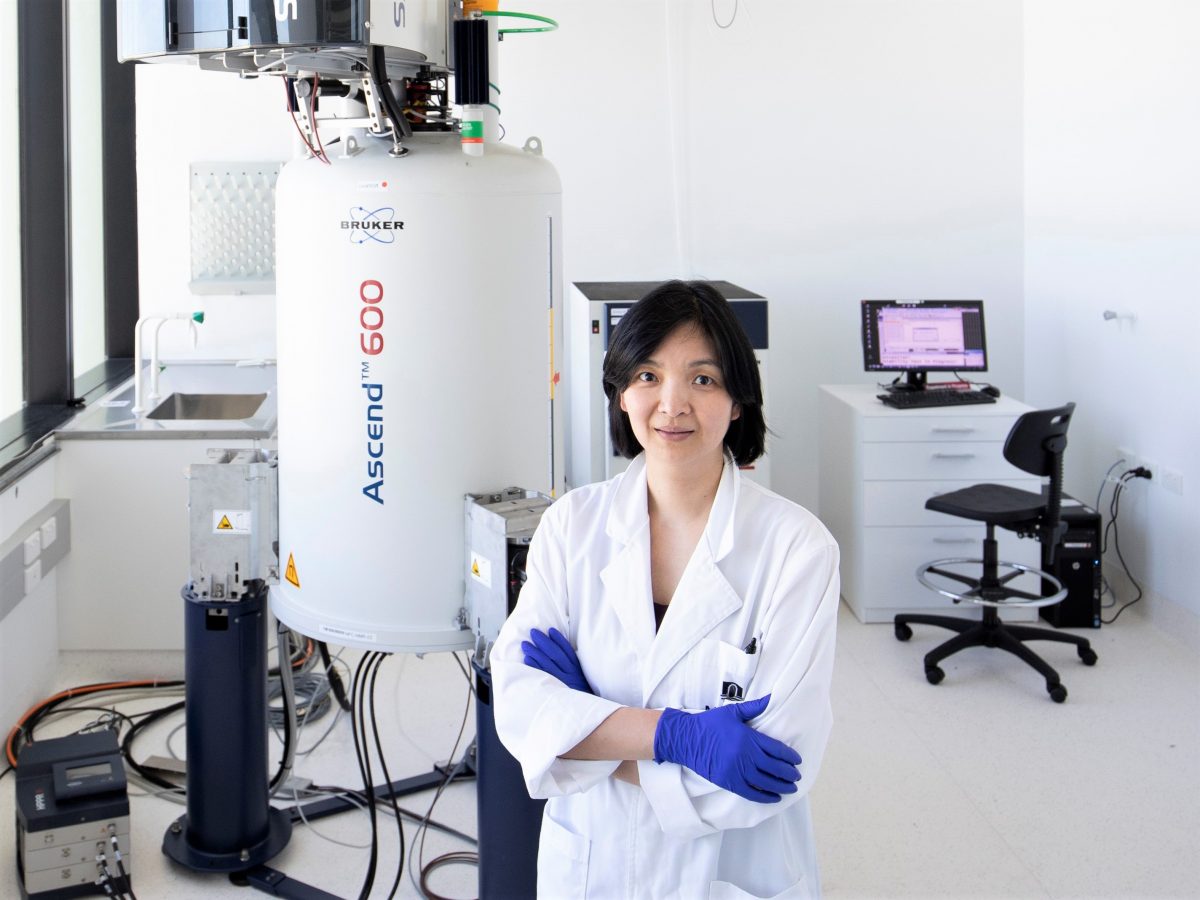

Dr Ruey-Leng Loo in the lab at the Australian National Phenome Centre on Murdoch University’s Perth, WA campus. Dr Loo is the research lead on the ‘WA Food metabolic library’ project under the CRC’s Research Program 3. Credit: Murdoch University

Checking out nutrition

Murdoch University clinical pharmacist Dr Ruey-Leng Loo works with Professor Holmes investigating what chemicals in food can play a key role in good health, and she is creating a “food library” of WA produce.

Alongside olive oil, Dr Loo is studying truffles and artichokes.

“We’re going to generate detailed chemical information of food and food products to verify their chemical make-up, nutritional functionality and other key attributes such as authenticity and freshness.” Dr Ruey-Leng Loo

She says by creating a molecular fingerprint of foods to know the chemical make-up of “high-quality” food, scientists can better monitor produce for authenticity and freshness.

Meanwhile, West Australian growers can use the science to market and sell their premium wares at a higher price on the international market.

It’s not just what you eat

Professor Holmes said she is studying how a WA version of the Mediterranean diet compares with the World Health Organisation’s recommendations for a healthy diet.

“We’re looking at why different people respond differently to the same food,” Professor Holmes said.

The team is focusing on people who are at risk of diabetes or metabolic diseases and has partnered with Imperial College London, in the UK, to see if they can tailor diets to help prevent or treat the disease.

“We know that one size doesn’t fit all when it comes to diet and some people excrete more calories in their urine than others.”

With the help of a mathematical formula, the researchers are doing blood analysis and using thermal energy to measure how many calories are excreted in a person’s urine. This quickly shows a person’s metabolic response to food.

That information can then be used to tailor a diet specifically for that person’s metabolism, which Professor Holmes says is dictated partly by an individual’s gut bacteria.

“There are a lot of metabolites that are different from person to person, and when you have differences in response to diet, it’s the gut bacterial-derived chemicals that we see that are different.”

This intricate understanding of an individual’s response to food types allows for health professionals and dieticians to tailor their advice with precision, rather than using broad guidelines.

She says some people who are at risk of diabetes because they are overweight or hypertensive may respond well to some dietary changes but not others, and that varies by person.

“We continue to work towards research which will uncover a pathway towards a healthy, disease-free population,” she said.

“The more we know about the microbiome, the more apparent it is that precision nutrition has a significant role to play in achieving in this.”

This article first appeared on the News section of Murdoch University’s website on 13 December 2021. It has been republished here with minor editorial modifications courtesy of the Murdoch University Media team. View the original article.

Lead image: Olive branch. Credit: Shutterstock